“It’s not the world’s prettiest heart” the barista sighs as she hands me my flat white. I just gape at her; has she got ultrasound vision? Can she hear the thudding inside? Is she priming herself to hop the bar and give me a cardiac massage with the tamper? Or not, I realise, smiling feebly, as she signals to the blotchy attempt at latte art.

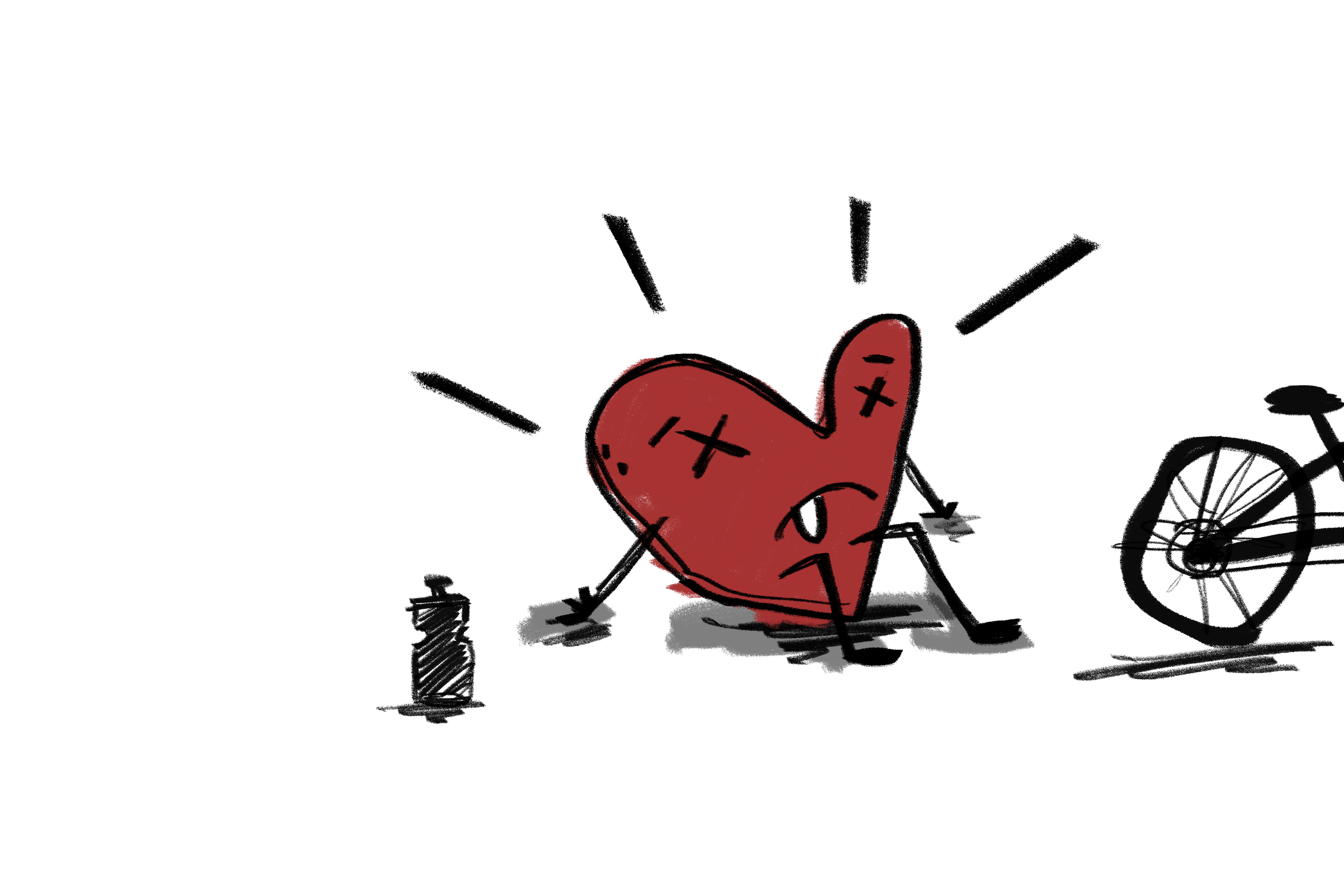

… it’s a foam heart; a romantic one, one that doesn’t beat, or have faulty valves or insufficiencies. Thirty minutes earlier I’d been lying on a hard bed with a cardiologist heavy breathing over my heart. Now I’m standing with a frothy broken heart, a piece of paper saying I’ve got tricuspid valve regurgitation, and question marks over whether I’ll be able to enjoy riding on the drops again in the same way.

Cycling is the ultimate lesson in upsell: you can always ride something that’s lighter, faster, better. New carbon layups and aero profiling are counterparts to smarter training and nutrition plans. Improve yourself and your bike. More watts mean more opportunities. Start riding today and in six months you can cross the Alps, in eighteen months you can be on the startline for the Transcontinental, because anything is possible. Cycling promises growth. Boundlessly naïve and optimistic.

My heart, once a showpiece, is now a sh*tshow

I’d never met a cardiologist before. Do you have any existing or prior illnesses? No, nothing. Do you take any medication? No. Do you exercise? Hell, yes. I’d taken a standard ECG that showed some “discrepancies.” My GP said that while it was pretty common amongst athletes because of our low resting heart rates, it was better to get it checked out. I nodded and puffed my chest out a little: athlete, tick, low resting heart rate, tick. If my heart is anything, it’s my body’s flagship organ, the one that continually overachieves, while my joints and muscles suffer in races and my liver occasionally gets a tough time of it. With every kilometre of training, I’m investing in a bright, rosy cardiac future. Every hill interval is planting a seed that’ll grow and bear fruit well into old age. Or at least, that’s what I’d always thought I’d been doing.

The tricuspid valve has three flaps. As your right ventricle pumps, the flaps close to separate the atrium from the main chamber. But if the flaps don’t close tightly enough, blood can leak back from the right ventricle to the right atrium. The more they fail to close, the more strain is put on your heart. In the majority of patients, a mildly insufficient valve can go unnoticed. But not always.

“Three out of four of your valves are fine,” explains the cardiologist, “but the fourth one isn’t closing completely.” They assure me it’s “nothing dramatic,” and that I can still do sport, moderately. I freeze. By “moderate”, they mean closer to 130 bpm than 155 bpm. I’ll require a check-up every two years. The image of my seemingly unstoppable heart shatters into a tangle of tissue, valves and tendons, writhing on the floor and whimpering with every beat. 130 BPM. A part of me cowers in shame at the way I’m overdramatizing it, but inside my internal cinema, I watch through my fingers as a man in a white coat buries my riding aspirations.

Hearts aren’t just any old organ. They represent activity, vitality, love, and most of all, life. Did I heap unreasonable expectations on mine? Did I start training too soon after having a cold? Did I invest so much in a healthy cardiac future that I overexploited myself? I gaze at the now even messier foam heart in the cup and think about what cycling is and will now become for me.

Drop bar detoxing

At the bottom of my cardiovascular hierarchy of needs is the physical act of riding a bike. Legs burn, heart races. You sweat, therefore you are. I’m not in cycling for the structured training with base miles and sweetspot intervals; I’m here for the pure exertion, the senseless burning of energy and the subsequent exhaustion.

On the level above, the door opens to the wonderful world of rewards. With each ride comes the anticipation of what comes next: a hot shower, a great meal, or a coffee. If I’m truly honest, the ratio of physical activity to reward has shifted heavily in favour of reward in recent years. Nowadays, even a short, steady ride legitimises a complex reward scheme of speciality coffee, cake, and jelly sweets.

From the third level and above, it’s no longer physical. Cycling makes me happy even when I’m not on the bike. My head is lost in Alpine passes, I plan bikepacking routes, fantasise over endurance events, and feel the warmth of the winter sun in Spain tickle my skin as I extract myself from thermal overshoes that are covered in mud. Cycling is a paradisiacal place that you can tap into at any time.

There’s a euphoria around cycling that is, quite frankly, jarring with the current state of the world. The economy is in crisis and the outlook for society is bleak, but you can work on your FTP and dream about gravel events. Riding has an ability to tap into emotions and experiences that will never fail to make you happy. It’s confirmation that everything’s fine and it will all work out.

Then at the top of the hierarchy of needs is the ultimate promise: eternal youth. It’s depicted inside the colourful graphs that display your fitness and freshness scores, and the personalised training plans that allude to new personal bests regardless of age. Can you cycle around the world at 70? If you so wish.

But here’s where I falter. Because having an enforced maximum heart rate doesn’t fit inside the promise of immortality. I sense it’ll raise more questions than answers. The cardiologist’s precautionary words come to mind each time I hear the familiar beep as I exceed 130 bpm. But the beeps don’t stop. They’re incessant. Carrying the bike to the third floor, beep. On a photoshoot with the rest of GRAN FONDO, beep, beep. Even the sight of the Stelvio’s altitude profile sets it off. Beep, beep, beep. 130 bpm means riding without breaking a sweat. 130 bpm doesn’t justify any sort of reward. 130 bpm puts an end to mountain passes. 130 bpm doesn’t make me excited. It’s not enough.

How sensible is it to avoid risks?

My news is met with mixed reactions: everything from well-intentioned “Listen to your body,” through to “What’s the issue, you can still ride” or “If you lose 10 kg and fix your diet, maybe you can compensate for it.” I don’t want to hear any of it. The only words I’m interested in are the ones that tell me everything’s okay and that nothing has changed. I decided to go for a second opinion.

I finally hear what I want to hear, but the diagnosis is still accurate. The tricuspid valve isn’t closing properly. But this cardiologist doesn’t talk about limiting the strain on my heart and the risks I run if I demand too much of it. This one speaks nicely to my athlete’s ego: I can – and should – do what I like.

This is where my article took a turn. Before I got the second opinion that brought my bike life back into balance, I’d planned on writing about what I’d learned. How you can approach cycling differently, how other things in life are so much more important, and how eye-opening this period of uncertainty was. I learned how much cycling means to me, and that I don’t want to have speed limits set on my body. I also realised that some diagnoses are not that straightforward. They can be ambiguous and leave room for interpretation. Avoiding risks at all costs may work for some, but for others it’s negotiable. I will still do every ride with a heart rate monitor, but I’m switching off the alarm for now.

Disclaimer: Any medical conditions depicted in this article are based on the author’s subjective opinion, may have been glossed over and underplayed, and should therefore not be taken as medical advice. For professional medical advice, consult a healthcare professional (or two, just to be certain).

Did you enjoy this article? If so, we would be stoked if you decide to support us with a monthly contribution. By becoming a supporter of GRAN FONDO, you will help secure a sustainable future for high-quality cycling journalism. Click here to learn more.

Words: Nils Hofmeister Photos: Julian Lemme