To understand the meaning of design, talk to an Italian. To understand the importance of bike helmets, talk to MET, who have established themselves as a guru on the topic of safety and, as an Italian family-run company, have safety-conscious design as their core premise.

There are high mountain peaks casting a shadow over the flat-roofed building. Unlike its geometric architecture, the line of shade appears dysfunctional and it heightens the feeling of remoteness to create a picture perfect embodiment of organic meeting mechanic. This is the world of MET, where connection – to nature, each other, fellow cyclists and their sponsored athletes – is everything.

Tucked in the mountainous valley of Valtellina in Northern Italy, is a sleepy town called Talamona. It’s where MET Helmets have called home since the early 1990s. Traditional villages dot the mountainside, while steep vineyards and steeper climbs (think Stelvio, Mortirolo, Gavia, San Marco and Bernina) have earned Valtellina a place in both wine and cycling history. Having garnered a reputation for their sophisticated and sometimes offbeat cache of helmets in numerous shapes, styles and colours that make a specialist in the genre, MET’s HQ sits serenely below the mountain peaks, making this steep-sided valley seem a sensible choice for the family-run Italian brand, who take inspiration from the rugged landscape rather than seeing the summits as natural barriers.

Contrary to how it’s perceived, MET is one of cycling’s few remaining small family-run businesses (although for Italy, this is nothing out of the ordinary with more than 85% of all businesses staying within a family). Its 30 employees are led by the husband-and-wife combo of Luciana Sala and Massimiliano Gaiatto, who set it up in 1986 from their hometown on the shores of nearby Lake Como. In terms of being a bike-helmet-only brand, MET is easily one of the oldest – after all, it wasn’t until the late 80s that helmets became a thing. Today, many of us would feel equally as naked riding without a helmet as we would without shorts.

Helmets are MET’s thing – it’s in their name (hel)MET. They’re no-nonsense about their family-run endeavour and have no qualms about eschewing conventional business wisdom that would suggest diversifying is the way to increase revenue streams. We caught a few words with Massimiliano Gaiatto, co-founder of MET, to get his take on their single-minded specialism: ‘If you only do one thing, do it well. Our goal is to make a valuable contribution to cycling rather than just having a commercial product. Of course, we need to stay afloat, but we’re confident that designing helmets for cycling is central to our future.’

The word ‘design’ echoes around the curated HQ, and the phrase that MET is a design company is something we hear repeatedly. But why does design matter when helmets are primarily there to protect us? ‘When you talk about design in Italian,’ explains Matteo Tenni, Product Manager and committed cyclist, ‘the interpretation is often limited to aesthetics, but the English way of understanding design encompasses the idea of functionality, ergonomics, aesthetics and everything else. That’s what applies best to our work. As designers, we design each helmet to fit a usage. That’s probably the biggest difference between a specialist helmet brand like us and a brand that might send off a design created by an agency to simply get produced.’

.

When we look incredulous, he comments that it happens more often than you’d imagine, with many brands considering helmets on a par with soft goods. His indignation continues for another few minutes, suitably affronted by the level of nonchalance that can be shown to a life-saving piece of equipment. Helmets have so many functions to fulfil in what is a very small package. They’re extraordinarily complex, he goes on, requiring very specific levels of protection, comfort, usability, aerodynamics, fit, ventilation and weight.

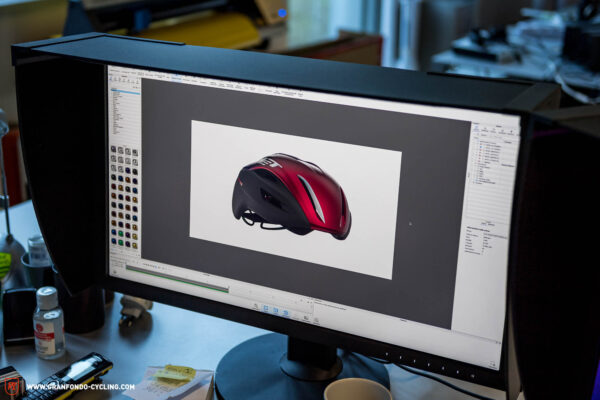

Judging by the sketches and renderings covering the walls of the design office, it’s easy to conclude that doodling a helmet is infinitely easier than producing one, otherwise MET could launch a new helmet every day. Deciding which helmets get developed is surprisingly complicated – and it’s a riddle that has captured the attention of renowned automotive designer Filippo Perini, who has worked with some of the world’s top brands including Audi, Lamborghini, Alfa Romeo and Italdesign, and now applies himself as Head of Design for MET. His sharp lines are central to their current, distinctive design language, and with 30 years of experience designing cars, he has famously commented that ‘it’s harder to design a helmet than it is a car.’

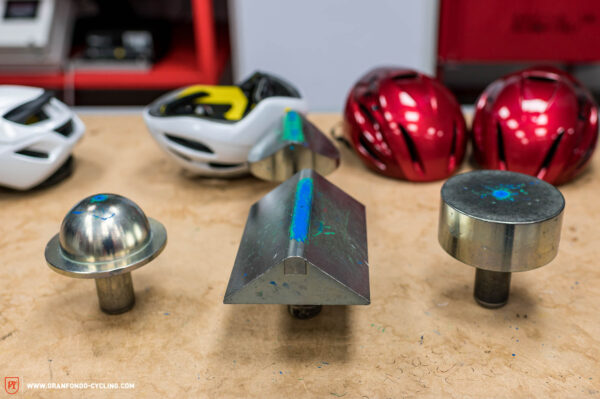

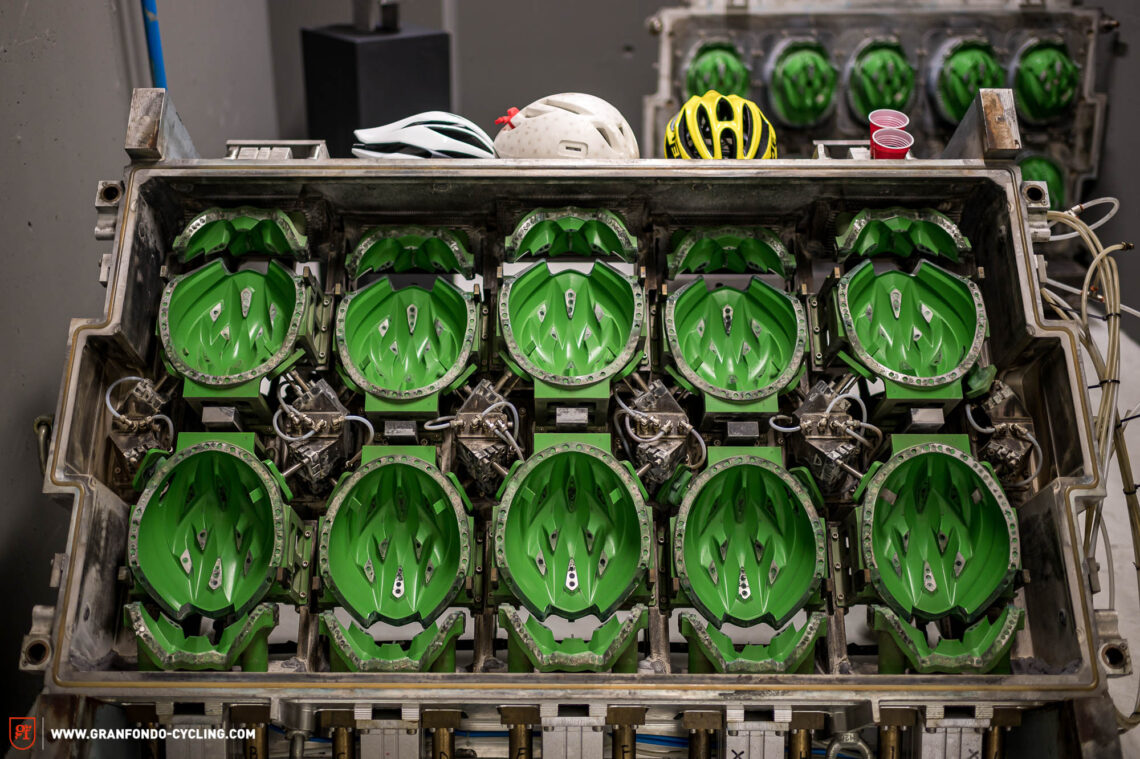

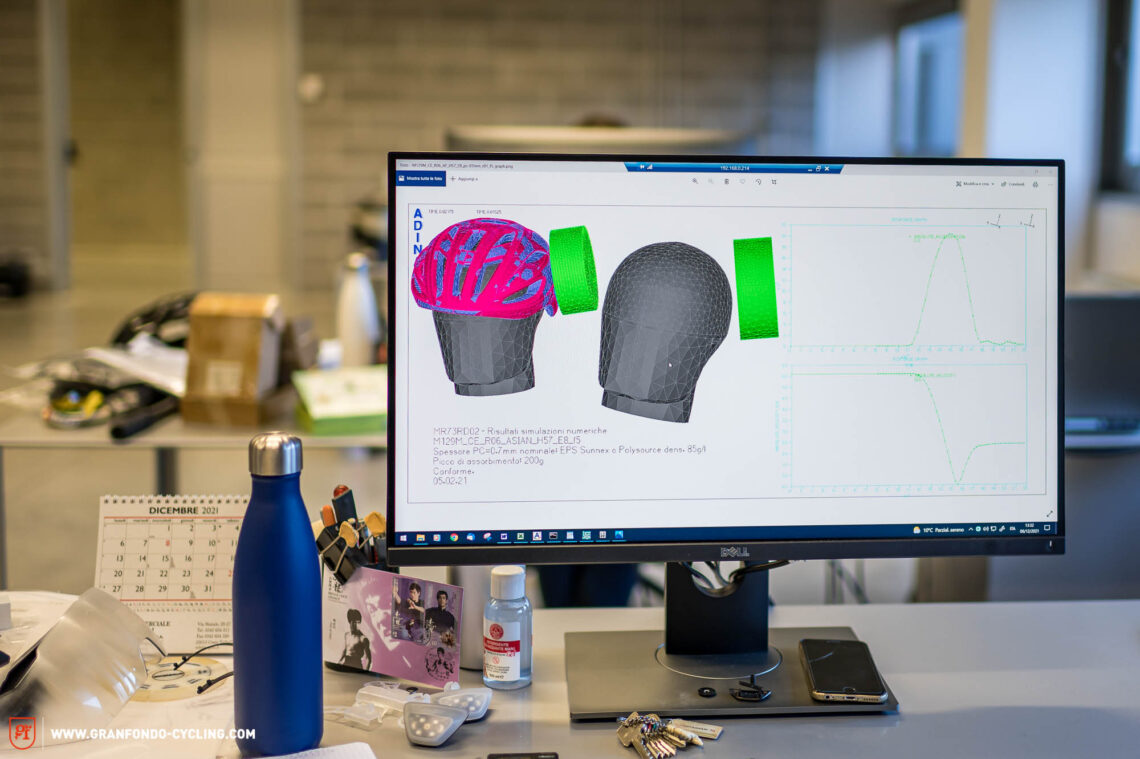

To be well-made, functional and fast, each helmet is launched following a long team effort. Ideation, prototyping and testing (as well as quality control) are all done in Talamona – it’s a mammoth task, involving all of MET’s departments, three 3D printers and a number of machines that could smash your skull, seriously overheat your head, and most probably cause your eyeballs to freeze. It’s not all fast designs and pencil drawings; being a specialist helmet-only brand involves masses of data.

No matter where you ride a bike in the world, your helmet has to satisfy a host of mind-boggling acronyms linked to their ability to safely withstand impacts from all angles. This is the part of the process that Cesare Della Mariana knows inside out. It’s this tall, athletic-looking man’s role in MET’s test lab as Quality Assurance to determine if a helmet meets the various certification levels. That’s because you can have the most amazing-looking helmet in the world, but protection in the event of a crash is what counts. Fortunately, Cesare’s work is made infinitely easier by the amount of pre-testing and informed computer modelling design that flows into each helmet. After all, at 35 years of age, MET isn’t going to waste time designing something that is anything other than fit for purpose.

From the hum of the test lab, we cross the spacious hall into the showroom, from where we peer out over another building that appears remarkably quiet. That was the home of production until 2012, when under mounting pressure, MET had to step up and make rapid changes to keep pace with the industry – ‘Even getting hold of raw materials had become a serious challenge,’ admits Matteo ruefully.

This outsourcing of production to Asia is something that comes up each time you speak to locals in the valley – particularly those from the bike community – but there’s no lingering wistfulness at MET and very few things that hint to their manufacturing past.

Despite everything that happened, MET – the present-day self-proclaimed design company – is happy to have gone through the upheaval and come out with the manufacturing know-how. With production being a universal language, this brand has been penning the lingo for over three decades, which means they were better placed than others when it came to outsourcing production – a move that often risks a loss of quality. For Matteo, who’s been with MET since 2001, their manufacturing expertise is as central to the design process as it ever was, even if he is no longer directly putting the helmets in the moulds he has made. The level of internal knowledge is something of a cheat-sheet, letting the team visualise what is feasible and how the production process would or could look like for a new model. ‘It’s our manufacturing background that guides us through the process – even if you can’t see the influence, you can feel it. With our MTB helmets, it’s self-evident how much has gone into a design and it’s easy to understand what drives the pricing, but often in the road sector we have to explain why a helmet is manufactured like this, and not style-driven,’ explains Ulysse Daessle, Head of PR. ‘That’s why we are so transparent about what we do, sharing how we work, because we believe in what we do,’ he continues with an openness that is not present in all brands within the cycling sector.

Of course, aesthetics are the final result that makes us purchase a helmet, but MET follows a process that accounts for everything a cyclist needs. ‘We’ve collected so much data through years of testing that we’ve collated a vast computer model that lets us go really deep into each design and forecast performance.’ Matteo is in his element as he explains their data-driven approach, looking at the impact resistance, ventilation and aerodynamic stats through a CAD simulation, which they then run through various 3D printers at different prototype stages. ‘Without our own internal lab, you couldn’t run these kinds of simulations. It’s intense work, but using lab data we’ve been able to calibrate a computer programme that really speeds up the process – especially when it comes to eliminating designs and, ultimately, fine-tuning them.’

But while the company’s technical success is largely built on data, the concept of constant dialogue is equally as critical. Calling Valtellina home since January 2017, Ulysse has recently become MET’s resident campaign photographer, in addition to his PR role through the support of the company: ‘I really like the mood here. Everything is collaborative and there’s a lot of opportunity to develop, and a lot of authenticity. You can create your own role and there’s a genuine freedom to propose ideas, which is not always the case at other companies. MET let you make mistakes and learn from them.’

It’s not that Ulysse made a mistake in his PR role, but he did buy a camera and get hooked on photography. ‘It began as a hobby when I picked one up in Japan, but MET has supported me fully. I like it, they like it.’ It is a refreshing take on how to run a business because even if many of the larger players in the cycling industry proclaim to do the same, their size naturally limits people to more fixed roles.

At 12:30 sharp, we ride across to the neighbouring town of Morbegno for lunch – a daily affair for much of MET’s young team. There’s a buzz as everyone gets on their bikes. Compared to other major cities in Northern Italy, Valtellina is somewhat of a backwater, so we discuss what it is exactly that draws the talent that has been amassed in the young MET team. Ulysse pauses to think: ‘We’re focused on getting young people. It can be a challenge, but I think it is the same for every industry. We’ve got the mountains on our doorstep, plus Switzerland and Milan within spitting distance. There’s no shortage of inspiration. When people decide to move here, you can tell they’re in it because they have values that align with ours.’

One interesting point that we could not overlook was how MET is faring with the current pandemic. Seeing that Talamona is not only one mountain range over from the areas hardest hit from Covid-19, but that MET is within cycling, which is experiencing a boom at the moment, it feels like it’s almost on the frontline. Ulysse continues over lunch: ‘It was not something we were particularly afraid of, but we were waiting to see what would happen. We didn’t cut any sponsorship because we knew we’d work together in the future. More than 10 new models have been launched since September 2020. Sure, we had to push back the Rivale launch by a couple of months, but it still happened. Now, like everyone, we’re having a bit of trouble with logistics, shipping, and delays of two-to-three months, including the not-yet-released Trenta 3K Carbon MIPS (you heard it here first folks). We had a massive increase in turnover and the new releases have helped massively. Working from home affected relationships here at work, somewhat. As you can see, we’re really into the easy nature of opening doors and asking each other questions. It was a strange time when we were separated, but I think we did the best we could.’

So many times companies can be broken down into statistics about their development and production, but that is just a matter of homework on details. The true story at MET is how the family-run entrepreneurial might behind the brand sees the merit in investing in its team, including the next generation of their family who are being bold, daring and fully collaborative, which makes us acutely aware of what a profound effect MET will have on the future of bike helmets. And judging by the past two editions of the Tour de France, we like the direction things are going in.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, we would be stoked if you decide to support us with a monthly contribution. By becoming a supporter of GRAN FONDO, you will help secure a sustainable future for high-quality cycling journalism. Click here to learn more.

Words: Emmie Collinge, Phil Gale Photos: Phil Gale