There are many decisions to be made before buying a new gravel bike. Speed or comfort? 650B or 700C? Shimano or SRAM? But if you’re seriously thinking about a new bike, there might be an even more important question. Should my next bike be a gravel bike at all or would a mountain bike be better?

Table of content

- The testfield

- Gravel or mountain bike?

- Geometry and riding position

- The testers

- Where did we test?

- The most versatile bike concept

- The competition

The gravel bikes of today are the mountain bikes of yesterday! This or similar sentiments all too often echo around the comments of posts and articles on the subject of gravel. Taking this into account, we’ve taken a fresh approach in our concept group test. Gravel: it’s that seemingly unpretentious space between roadies and mountain bikers. A calmer realm where trail rider meets road cyclist to celebrate lightweight bikes and their agility and speed. The common platform where die-hard roadies leave the asphalt behind and celebrate a whole new experience of nature. But are gravel bikes really that different from the mountain bikes of yesteryear? Where does mountain bike terrain begin? Where does gravel end? Should I even buy a gravel bike if I want to have fun off-road or should I swap my trail-fully for something more nimble? Might the answer be in the middle and are mountain bike hardtails the perfect middle-ground or a washed-out compromise?

This isn’t just a bike test – We compare concepts based on six representative examples.

For this group test, we have put 6 bike concepts under the microscope and to the test. Each bike is the representative of a certain category and for each of these bikes, there are countless alternatives on the market. So our aim here is not just to compare the bikes themselves, but to find out which bike concept is actually the most versatile. The potential range of uses is wide, as we test on everything from asphalt to gravel, forest tracks and trails. We tell you which bike concept will suit you, while the test winner is the concept that successfully covers as many uses as possible.

The test bikes at a glance

While putting together the test field, we picked out what we consider to be the most progressive and innovative representatives of the individual genres covered. We are of course interested in how the bikes ride, but much more important is the question of how the respective concept performs on our test track and how versatile they are in practice.

The brand new BMC URS LT, the Canyon Grizl CF SL 8 1by the FUSTLE Causeway TRAIL Lite and the Lauf True Grit represent the drop bar group, though each bike positions itself slightly differently. While the URS LT represents all full-suspension gravel bikes, the Fustle Causeway represents unsuspended gravel bikes with progressive and mountain bike inspired geometry. The Canyon Grizl represents the classic, rigid “European” gravel bike. The Lauf True Grit is a gravel bike hardtail with a suspension fork, featuring the brand new SRAM XPLR collection.

The BMC Twostroke 01 ONE and Trek Supercaliber 9.8 GX fly the flag for mountain bikes and flat bars. The former puts stock in progressive geometry with a long reach, a slack head angle and a short stem, a geometry trend that can be seen in numerous new cross-country hardtails. The Trek steps it up and represents full-suspension mountain bikes. That said, with its shock integrated into the frame and the pivotless rear triangle, it occupies a unique position in the diverse field of full-suspension mountain bikes.

Of course, our stand-ins can’t adequately represent the entirety of their respective bike genres. As a “gravel-fully” the BMC URS LT only has elastomer suspension on the rear triangle, while the Trek is a cross-country race bike that will never be able to substitute a trail or enduro bike. Nonetheless, this isn’t relevant for clarifying the question of where gravel ends and mountain biking begins. Gravel bikes with less reserves than the Canyon push their range of use as much in the direction of asphalt and speed as mountain bike fullys with more suspension travel do in the direction of trails and off-road.

Below you’ll find an overview of our test field. Particularly exciting: the difference in weight between the lightest and heaviest bike is equivalent to just 2 filled water bottles. Some gravel bikes actually end up heavier than the mountain bikes! All test bikes use a 1x drivetrain and there is relatively little difference in tire dimensions. All bikes roll on 700C/29” wheels, and while the overall diameter varies significantly depending on the tire fitted, there’s just 17 mm between the narrowest and widest tire.

| Model | Groupset | Wheelset | Tire size | Weight | Price |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMC Twostroke 01 ONE (Click for review) |

SRAM GX Eagle AXS | DT Swiss XR 1700 SPLINE | 29″ x 2.35″ | 9.89 kg [L] | € 5,499 |

| BMC URS LT ONE (Click for review) |

SRAM Force eTap AXS | CRD-400 SL Carbon | 700 x 40C | 9.52 kg [L] | € 7,999 |

| Canyon Grizl CF SL 8 1by (Click for review) |

Shimano GRX RX800 | DT Swiss G1800 | 700 x 40C | 9.12 kg [M] | € 2,699 |

| Fustle Causeway TRAIL Lite (Click for review) |

Shimano GRX RX800 | HUNT 4 Season Gravel Disc X-Wide | 700 x 45C | 10.04 kg [M/L] | € 3,500 |

| Lauf True Grit SRAM XPLR Edition (Click for review) |

SRAM XPLR AXS Rival | ZIPP 303 S | 700 x 40C | 9.82 kg [L] | € 5,750 |

| Trek Supercaliber 9.8 GX (Click for review) |

SRAM GX Eagle | Bontrager Kovee Pro 30 | 29″ x 2.20″ | 10.6 kg [L] | € 5,499 |

| Ø 9.83 kg | Ø € 5,158 |

This test field is undisputedly the most diverse we have ever put together at GRAN FONDO. What might seem out there at first glance, only makes sense considering some of the latest product launches. More gravel-fullys will no doubt be announced by numerous manufacturers. But is there a need for such products, when the market already seems to cover so many niches? Our test field attempts to reflect and unite the genres of bikes that would best cover the spectrum of road, compact and loose gravel, forest tracks and full-on trails. So, once again we are in search of the holy grail: the bike for everything, the ultimate all-rounder, the one-bike quiver. Gravel bikes are just one answer to this but gravel does not mean the same thing to everyone or everywhere. Why is the definition of gravel so diverse? Here’s an attempt to explain.

Not all gravel is created equal: USA vs. EU

A headline that might seem like a terrifying premonition of a Cold War 2.0 is actually much less dramatic. Nonetheless, the basic understanding of gravel riding is often different in the US and Europe. The Americans are only too happy to portray themselves as the forefathers of the gravel trend and paint a picture of 10-metre-wide gravel highways that run dead straight through remote wilderness for thousands of kilometres. High speed on the solid, compact gravel tracks, dust clouds and stylish neckerchiefs – a light and liberating aesthetic that was all too tempting for sections of the rule-abiding road bike community in Europe. So, a few years ago the gravel boom exploded on this side of the Atlantic and with races like the cobbled (and sometimes gravel) classics in France and Flanders, beach races in the Netherlands and the tradition-steeped Strade Bianche in Italy, it was easy to feel like founders of the gravel movement here too.

The enthusiasm was and still is huge, but when gravelling in Europe, one quickly realises that gravel rarely consists of straight, 10 m wide, compacted highways. Dust clouds, wild and barren landscapes, cacti? Not a thing! Instead, agricultural tracks and forest paths, back roads and side roads – broken asphalt, mud, rocky trails, fist-sized stones, tight corners. For many European gravel fans, products such as aero or race gravel bikes aren’t the most relevant for their daily ride between allotments and cow pastures. Versatility seems to be the key! On the other hand, the gravel crew between Kansas and Oregon frowns on chunky bikes with suspension and drop bars. All they need is a bike that lets them fly over the fire roads at 25 mph (≈ 40 km/h). 60 mm deep aero rims? A must!

The limited prevalence of perfect gravel highways in Europe and the characteristics of the local trail network are, however, only one reason why gravel bikers are increasingly driven into what was originally reserved for mountain bikes. Underbiking also plays an important role!

Gravel or mountain bike? From underbiking to overbiking

Underbiking is when you ride more demanding terrain than what your bike was originally intended for, for example, taking a gravel bike onto mountain bike terrain. Unlike the aforementioned shift from gravel to mountain bike terrain as a result of necessity in Europe, we are talking about a conscious decision: off the gravel road and onto the trails. Experienced riders can turn their familiar local loop into an exciting ride again. Of course, to a certain extent, races like Strade Bianche, Paris-Roubaix or the gravel sections of the Tour de France can also be considered underbiking. It should also be clear that this isn’t something for beginners or a relaxed ride where you just want to switch off! The demands on riding technique and physical fitness are high here.

Overbiking is the exact opposite and refers to situations in which a bike with additional reserves is left under-challenged during a ride – an extreme example would be riding an enduro mountain bike on an asphalt bike path. If in doubt, overbiking is the more sensible option for most people, as it usually leads to an increase in safety. Although gravel bikes are very versatile by definition, it can happen that your bike ends up both under- and over-equipped on the very same ride – because the route is simply even more versatile than the bike. However, the trend will always go in the direction of underequipped, since experience shows that many riders continue to develop further, as well as delving ever deeper into unknown terrain. Manufacturers take this into account by trying to make gravel bikes as versatile as possible with components such as suspension forks and to expand the range of use sensibly – because in case of doubt, a bike should rather be over- than underequipped.

With this group test, we want to answer the question of whether mountain or gravel bikes are the better accomplices for these adventures, to whom they are best suited and where the strengths of the individual concepts lie. But before we get started, it’s important to get to grips with the basics of suspension. That’s why we’ve enlisted the help of the mountain-bike-clued-up editorial team at our sister magazine ENDURO to explain the crucials.

Hardtail? Fully? Everything explained

It was only a few decades ago that the question, “Suspension or not?” wasn’t even a consideration. The first mountain bikes, like many conventional gravel bikes today, were completely rigid. With the use of suspension forks, these bikes developed into so-called hardtails. Nowadays, thanks to sophisticated suspension forks, mountain bike hardtails like the BMC Twostroke with 100 mm travel can be very competitive in terms of performance, even without suspension at the rear. Gravel is another area where not only terminology but mountain biking technology is catching on. While most gravel hardtails rely on much less travel up front, the basic principle remains the same. One example is the RockShox Rudy Ultimate suspension fork with 30 mm travel, fitted on the Lauf True Grit SRAM XPLR Edition.

Fullys i.e. full-suspension mountain bikes, are bikes that have both a suspension fork and suspension at the rear. In mountain biking, this consists of a shock and suspension linkage that allows the rear triangle and wheel to move out of the way of obstacles. The Trek Supercaliper with its integrated shock isn’t immediately recognisable as a fully, but it nonetheless relies on the concept. The first fully gravel bikes have also appeared. However, instead of a heavy shock and complex kinematics, they usually rely on simple suspension elements that generate just a few centimetres of travel, like the BMC URS LT with its Micro Travel Technology.

Both forks and shocks are high-tech products in the mountain bike world and rely on damping in addition to a spring. The stiffness of the spring can usually be adjusted to the rider’s weight via the air pressure. This is crucial because the correct sag i.e. how far the fork/shock compresses under the rider’s weight is essential for best performance, because a fork/shock must also be able to rebound during riding in order to maintain contact with the ground (i.e. maintain traction). While the spring ensures that the wheel can compress or rebound, the damping controls the speed of this movement during compression (compression damping) and during extension (rebound damping). Systems without damping lack this control, meaning the suspension travel is used up much too quickly or bounces harshly. No matter whether it’s a fully or hardtail, the best suspension system is only as good as it is adjusted to the rider (weight, height, riding style).

In addition to spring rate, mountain bike systems have dials to adjust the amount of damping. Lockout, to stiffen up the fork, is also usually part of the compression damping. Even though the technology is complex, heavy and expensive, the first examples can now also be found on gravel bikes. However, many manufacturers rely on simpler systems, made of elastomers, which provide both the function of the spring and, through their internal friction when compressed, a certain amount of damping. However, to really adapt them to the rider, the elastomers have to be changed.

What is compliance and how does it benefit me?

When we talk about compliance at GRAN FONDO, it usually refers to the comfort that a certain component or the bike concept as a whole offers through intentional flex and its construction. Frames or individual bike components have meaningful compliance when they not only flex, but dampen this in a predictable manner, as is the case with the suspension elements of a hardtail or fully. Let’s take the example of handlebars: if compliance is insufficiently damped, you feel like you’re holding a nervous pogo stick in your hands. So good compliance doesn’t just mean flex in a component but always includes its damping. Between too stiff and too soft, indirect and spongy, lies the sweet spot that should be suited to the particular application of the bike. The problem is that what might be extremely harsh for small and light riders, passing on all vibrations almost unfiltered, might deliver just the right amount of comfort for a heavy rider. Some bike brands adapt the frame compliance, for example by adjusting the carbon layup, to each frame size. This is expensive and complex, yet still ignores people who fall outside the norm in terms of weight: 2 m tall flyweights and 1.50 m small musclemen aren’t usually taken into account by the manufacturers.

After decades in which the world of drop bars was all about absolute stiffness at the lowest possible weight, many bike manufacturers have realised the advantage of compliance and increasingly rely on flex in exactly the right places. After all, stiffness is essential for steering precision, high-speed stability and propulsion. Thus, BMC rely on special tube shapes and carbon layups for the Twostroke hardtail, in combination with a compliant seat post, to offer a lot of comfort at the rear. For bikes without a suspension fork, compliance in the fork and cockpit also plays an important role. The flex results in a certain amount of “travel” at the handlebars, which might not iron out potholes and vibrations but can take away some of their terror. This type of compliance is all about vibration damping and this is best when the compliance-giving components are cleverly and holistically matched. For example, a handlebar with a lot of compliance in an otherwise very stiff bike can feel unnatural and vague. But if the cockpit, wheelset and tires are all small compliance sources in their own right, the result is more balanced riding performance.

Active suspension: Comfort vs. traction

When it comes to a bike’s suspension, it’s not just a question of whether it’s a fully or hardtail, but also whether the suspension element is intended to increase the bike’s traction or comfort. The combined dropper and suspension seat post, the RockShox Reverb AXS XPLR, is primarily for increasing seated comfort rather than traction in its Active Ride mode, while the Trek Supercaliber’s rear suspension makes rolling over obstacles both easier (traction) and more comfortable. Even a suspension stem like the Redshift ShockStop (read review here) or the Vecnum freeQENCE, while offering a similar amount of travel to the Rock Shox Rudy, can’t deliver the same performance. Although they offer about the same travel, they merely decouple the rider weight from the bike, leaving the unsprung mass higher. It should be obvious that the lines between comfort and traction are blurred. But the crucial questions are where the travel is generated and what the ratio of sprung to unsprung mass is. A suspension system generates the most traction when it allows the rider, or their centre of gravity, to maintain as smooth a movement possible, while the tires track the rough, uneven ground below.

Where and how much travel is generated, and what is the ratio of sprung to unsprung mass?

At this point it’s time for a little self-reflection, because you yourself are the heaviest component of your bike system, but can also provide the most suspension travel. Your arms and legs can, if you let them, act as a spring and damper to absorb really big impacts without any problems. However, the basic prerequisite for this is that you have enough freedom of movement on your bike. In the front, the handlebar ergonomics play a decisive role: if you’re in the drops on a drop bar, your elbows are already bent, so that your arms can only function as suspension to a limited extent. The situation is different with the wide mountain bike handlebars from BMC or Trek, which automatically put you in a kind of push-up position, from which you can use your entire upper body (chest, shoulders and arms) to absorb shocks and generate a lot of “travel”.

BIt’s a similar story for the legs, because one thing is clear: if you can climb the Stelvio or master the Unbound Gravel Race, you’ll also have enough muscles in your legs to absorb really big shocks from roots and stones as soon as the gravel highway turns into a rough trail. The problem: quite a few bikes in the test don’t give you enough freedom of movement with their high saddle to make use of the suspension travel available from your legs. Besides the obvious components like the dropper posts on the True Grit and the FUSTLE Causeway, the seat tube angle of bikes with rigid seat posts affects your freedom of movement when standing. The BMC Twostroke with its particularly steep seat tube angle of 75° offers only a few centimetres of free space between your bum and saddle when standing, while the Trek with its slack seat tube angle of 71° offers twice the freedom of movement. Whether steep or flat, if you want to fully exploit the potential of your legs not only in the fight against gravity, but also in interaction with it, you can’t get around having a dropper post with several centimetres of travel. Unfortunately, the disadvantages of using a dropper post are the significantly higher weight compared to a normal seat post (positioned higher up on the bike), the higher complexity due to the extra controls and an increase in stiffness which can have a negative effect on comfort when sitting. As always, there’s a compromise involved.

The difference between gravel and mountain bikes: Geometry and riding position

As we’ve already established, suspension and the type of comfort and traction sources available are hugely different between gravel and mountain bikes. We’re now concerned with both the geometry differences between the two bike worlds, as well as the differences in terms of riding position both in and out of the saddle. Is it possible to determine the diversity of gravel bikes and mountain bikes based on their geometry?

With this group test, we want to find the most versatile concept that can convince in the most diverse areas of use. Initially, one might assume that mountain bike geometry is advantageous for all off-road uses, while a geometry setup that is kept as close as possible to a road bike can convince on the road and compact surfaces. Should that be the case, we need to consider what the most important geometry values are and what influence they have (on paper) on the handling. Can we even tell which bike works best where just by looking at geometry?

What geometry tables tell us – and what they don’t

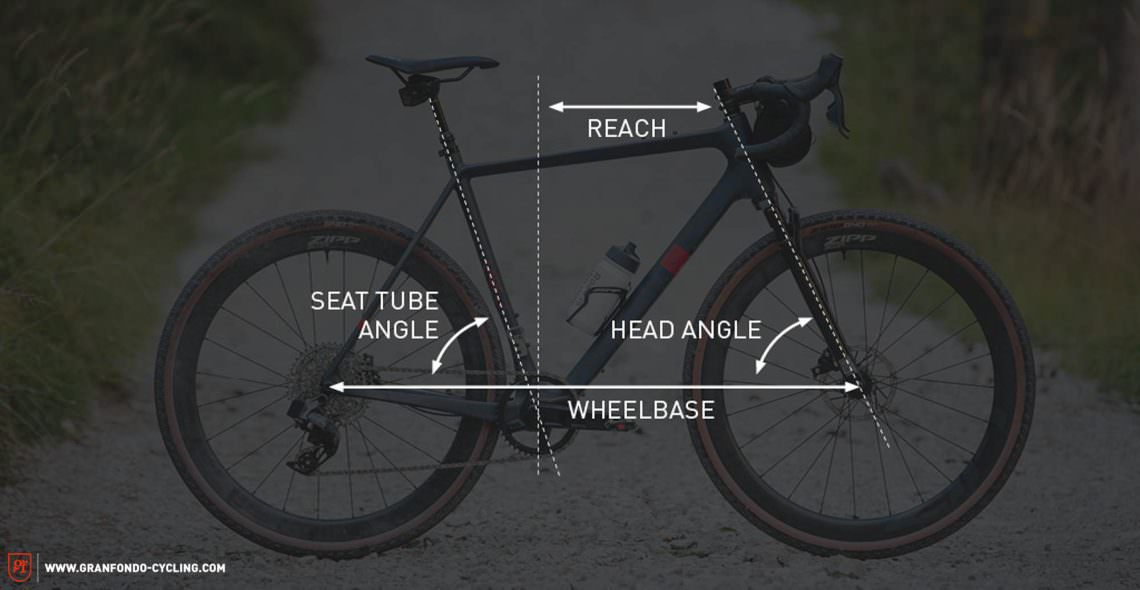

We’ve picked out three values that are often deemed to be decisive factors for the handling and riding position of a bike: reach, seat tube angle and head angle. For each of the three values, we will show you below why they say little when considered in isolation.

Reach is one of the most pronounced differences when comparing the geometry of mountain and road bikes. It is also often the source of endless discussions and confusion. Modern mountain bikes have a longer reach, between 430 and 485 mm – on progressive enduro bikes it can be over 500 mm depending on the size. Gravel bikes usually have a reach of 370 to 425 mm. However, how stretched or compact your position is on the bike has less to do with the reach than you might think. A short stem and a steep seat tube angle can lead to the same position on a bike with a long reach as on a bike with a short reach, long stem and slack seat tube angle.

In the words of bike-fitting guru Bastian Marks, “To me, the reach is more to do with handling and definitely very important. A certain reach makes the bike ride better and more stable in the corners. However, looking at these things in isolation is a problem. For me, the reach ignores the most important fitting factor, which is the seat tube angle.” You can find out more on the truth about bike fitting here.

The reach alone does not define your position!

When it comes to the seat tube angle, we distinguish between steep, from 78° to 73°, and slack seat tube angles, between 72° and 70°. The seat tube angle is usually defined as the angle of the line going from the centre of the bottom bracket to the centre of the opening of the seat tube. However, the precise angle can vary slightly given that the seat tube rarely opens up straight into the bottom bracket. Steep seat tube angles have an advantage, especially uphill, because you tend to sit a little further forward which lets you keep more pressure on the front wheel to keep it planted. Their disadvantage is that the forward position puts more pressure on the hands, which can lead to discomfort, while the positioning of the knees can also cause problems. Often, a very steep angle also results in less compliance from the seat post and tube.

However, any discussion about seat tube angle needs to be given context for large saddle extensions or kinked seat tubes, as you’ll often find on mountain bikes. For the latter case, the real seat tube angle will end up slacker than the one specified by the geometry – the mountain bike sector now works almost exclusively with the effective seat tube angle, i.e. the virtual line formed between the centre of the bottom bracket and the top of the seat tube, rather than taking into account kinks in the seat tube. This means that as the saddle is raised, the apparent seat tube angle becomes slacker. As a result, you are positioned further back on the bike and the front end will lift sooner. It’s also important to note that you can adjust the fore/aft position of your saddle significantly by sliding it on its rails, changing the effective seat tube angle by around 2°.

As such, on mountain bikes the saddle height becomes a defining factor for the seat angle which also makes it impossible to compare geometry between mountain bike models. On the other hand, on gravel bikes the actual geometry defines the seat angle. However, as mentioned, these don’t always correspond to the angle of the seat tube. As such, we claim that comparison isn’t meaningful! In any case, the seat tube angle loses its meaning anyway as soon as you get out of the saddle for the so-called riding position (or for sprinting, if you’re a roadie).

When riding downhill the influence of the head angle on the bike’s handling becomes apparent. That said, considering it in isolation ignores factors such as fork offset and trail. Nevertheless, it describes how far in front of you the front wheel is positioned. The steeper the slope, the safer you’ll feel with a slack head angle. But even on a flat trail, the longer wheelbase of a bike with a slack head angle makes the bike feel more stable and smooth. This is noticeable both on fast trails and at high speeds on the road or forest highway. The bike becomes less susceptible to small impacts or crosswinds, but also requires noticeably more steering input to avoid obstacles. In addition, bikes with a slack steering angle tend to have a vague feeling front end at low speeds that feels like it wants to flop from side to side. With a steep head angle, the handling becomes very direct. With such “fast” handling, you can skilfully avoid roots, potholes or car doors. However, at high speeds such bikes require a guiding hand and delicate steering input.

Precise geometry specs are of no use if they are misunderstood

Geometry data is least meaningful when it is misinterpreted by the reader. As mentioned, the reach of a mountain bike has little relevance for the seated position and on a gravel bike it is only one of many factors. To reduce the handling of a bike to a single geometry number is fundamentally wrong. The individual aspects of geometry influence each other. For example, the smoothness of a bike is not only determined by a slack steering angle, but also by the bottom bracket height, the length of the front triangle, the chainstays and the offset of the suspension fork. Of course, suspension is also a crucial factor.

Important: comparing the geometries of mountain and gravel bikes is complicated and does not make sense without expert knowledge. Understood correctly, geometry tables can be indicators for the range of use of a bike. However, in practice the performance of the bike depends on many other factors too – spec, cockpit setup, saddle setting, weight distribution, suspension setup, tire pressure, etc.

And it gets even more complicated, because the geometry data of mountain bikes refers to the non-compressed suspension state. Particularly with full-suspension bikes, the rear end has an enormous impact on the geometry and this changes as soon as you sit on the bike. For example, if a bike has high anti-squat that lifts the suspension under chain tension, then the seat tube angle ends up being steeper uphill than on a bike that sags under load. More on this topic can be found in our sister magazine ENDURO in the article “The great confusion” (read it here).

What role do tires play on gravel and mountain bikes?

Tires are the only contact point to the ground on all bikes and are a crucial component. But one key thing becomes clear when comparing mountain and gravel bikes. The tire on a gravel bike is akin to the suspension of a mountain bike. What does that mean? On modern full-suspension mountain bikes it is not uncommon to find adjustment options for high-speed and low-speed compression damping, rebound damping, air spring volume and air pressure – and all this for both the fork and shock. This means that you not only have numerous adjustment options for the damping, traction and comfort of the bike, but you can also influence its handling in certain situations.

On a gravel bike, the tire has to take over all these tasks. Its attributes are the biggest adjustments that are available here. However, changing the wheelset/tire system on a traditional gravel bike is significantly more expensive and cumbersome than simply turning the blue compression screw of the suspension fork on a mountain bike. Nonetheless, for those who do not want to use a suspension fork, tires remain the best and most effective upgrade for a bike. If you’re looking for a gravel tire, make sure not to miss our extensive gravel tire group test (read it here) with the 12 most important tire models compared.

Tires are the best and most effective upgrade on your bike.

Different wheel dimensions also have a significant influence on the area of use of a bike. Here we can generally distinguish between the smaller wheel size i.e. 27.5″ or 650B, and larger 700C or 29” wheels. The equation 700C = 28″ = 29″ is both correct and incorrect in this context, because all three designations refer to the outer diameter of the rim. The inner diameter of the tires (= outer diameter of the rim) is identical at 622 mm. However, since the tire volume also increases with increasing tire width, the tire outside diameters vary. Our article “Finding the right wheel size on a gravel bike – 700C and 650B battle it out” sheds more light on the differences between the individual wheel sizes.

The range of gears and their influence on the range of applications of gravel and mountain bikes

On mountain bikes, 1x drivetrains are now the norm, and rightly so. The majority of gravel bikes now also have them. Cassettes with a generous 10–52 t range, currently only achieved by SRAM Eagle, offer a similar gear range to a 2x drivetrain and significantly simplify shifting off-road. In addition, the maintenance requirements are lower, the susceptibility to mechanical issues minimised, while wear and weight are reduced. However, there is one disadvantage. Jumps between gears are significantly larger than with 2x drivetrain, especially with huge 10–52 t cassettes. With the 2x setup, you have small gear jumps and can often pedal the perfect cadence, while the jumps are larger with the 1x system and you pedal a little too hard or too easy when in doubt. The trade-off between the two systems is as follows: size of gear jumps vs. complexity of shifting, wear and weight.

The classic drivetrain with two chainrings and a smaller cassette still has its place on gravel bikes. One example is the Shimano GRX RX800 2×11 gravel groupset (read review here). Particularly on bikes that are used at least 50% on asphalt, the smaller gear steps are very sensible. Even 1x drivetrains with smaller gear steps, such as the SRAM XPLR groupsets (read review here), can make sense on asphalt, as long as you’ve found the chainring size that matches your riding. In any case, one thing is clear: the shifting system used and how it is tuned both have a big influence on the bike’s range of use! Ultimately, the trade-off you have to make is always the size of the gear range in relation to the size of the gear jumps. Or to put it another way, you have to decide whether you want the right gear for any terrain, no matter how steep, or always want to be at the right cadence.

This is where opinions differ: Drop bars or flat bars?

Curly bar, drop bar, race bar – no matter what you call them, hardly any other component is the subject of so much discussion and better represents the border between mountain and gravel bikes. Apart from John Tomac’s historic crossing of the line in the 90s, drops bars can also be found on bikes with mountain bike setups at off-road bikepacking events like the Silk Road Mountain Race.

And for good reason, because drop bars offer numerous different grip positions. On top of that, they let you change your position and angle of your upper body. This makes it possible to change the virtual top tube length and the distance from your contact point with the saddle to your contact point with the handlebar, leaving you almost with three different bike geometries in one. In addition, the different grip positions allow you to adjust your aerodynamics to the riding situation and change the weight distribution on the bike without having to get out of the saddle. Additionally, for many of you, the drop bar is probably just the tool you’re used to. #dropbarsnotbombs

The biggest pro of the drop bar is the biggest con of the flat bar.

So what’s wrong with the drop bar? It gets tricky in riding situations where an upright upper body is required – e.g. steep downhills. For maximum bike control the lower handlebar position is a good choice, but with it the centre of gravity comes very far forward, your head lowers and you end up looking directly at the front wheel. Lack of foresight when riding and a greater tendency to flip over the bars are the result. In handlebar positions where the upper body remains upright, the brakes are either inaccessible or difficult to operate. A higher grip position within easy reach of the brakes would therefore offer an increase in safety.

In exactly these situations, flat bars know how to shine. Here, braking with one finger is possible at any time and thus enough fingers remain for a secure grip on the bars. Its longer lever arm (because it is wider) also offers more control in tricky situations. There is only one grip position on the flat bars and thus the handlebar can be specifically optimised for this position. This way, the riding position can be optimally balanced and adjusted with regard to the desired performance. Simultaneously, this is also the biggest disadvantage of the flat bar. A variation of your hand position is, if at all, only possible to a limited extent. This means that you sit locked into position and can only react to the current riding situation by changing your body position. This relatively static position and associated muscular strain will be unusual for roadies.

How and who tested? The testers and what matters

Special times call for special measures – and a special test field calls for special testers. In keeping with the occasion, our test crew was as diverse as the bikes themselves. What makes them tick and which bike from the test suits them best? Curtain up for the test team!

Chief of testing, Suspension nerd and enduro racer

Felix tests over 100 bikes a year, combining that with his vast experience and Master’s degree in Sports Engineering. A coherent overall concept is the key to success for him. For him, the FUSTLE Causeway is the perfect fun machine. It knows no compromises on the downhill, goes uphill willingly and, for once, doesn’t need any suspension to be set up before the ride.

Editor GRAN FONDO, Road racer and mountain bike newcomer

Tobi has been doing structured training for a few years now. Podiums at licensed German races? Placing in the top 5% at the Ötztaler Radmarathon? Not an issue! On the Trek Supercaliber he is able to reel off long training sessions as well as turn onto the trail with sufficient reserves to tackle it. With his race bike and his crosser, it’s the perfect 3-bike collection.

Landscape architect, Cardio fan and all-round ace

When Nina isn’t busy planning the greening of the cities of tomorrow, you can find her out in nature on all kinds of bikes. She has given up her road bike in favour of the gravel bike. For boundless discovery tours, smooth handling, comfort and sufficient reserves are important to her. The BMC URS LT combines touring comfort with great handling and is therefore her first choice.

Art Director GRAN FONDO, Surfer and bike-tech philistine

Julian has already explored the Pacific with sharks, shaken hands with his fear of heights in the Himalayas, spent a few hours in the oldest prison in Uruguay and found world peace in the Brazilian rainforest. As a digital nomad, he has travelled half the world and done the layouts for our magazines at the same time. He doesn’t want to worry about his bike, just get on it and ride off. The FUSTLE was the best way for him to do that.

Founder GRAN FONDO and ENDURO Magazine

As a former Downhill World Cup racer and Dolce Vita expert, Robin knows how to find the balance between speed and flow. He’s the first one awake, the last one in bed and always in the office before the others. With a lifestyle like that, you need the right bike to balance it out. The versatile Lauf True Grit is up for any kind of fun and puts a big grin on his face – whether on relaxed tours, on gravel roads or on flow trails.

Editor-in-chief of GRAN FONDO and DOWNTOWN, Gravel aficionado

With roots in downhill racing, Ben likes to let it rip off paved trails. Even though as GRAN FONDO editor-in-chief he mainly rides with “narrow” tyres on asphalt and gravel, he wants a bike with defined suspension and strong downhill capabilities when it comes to wilder trails. With the BMC Twostroke, he has the most fun on trails and can also maintain a 28 km/h average on gravel roads.

Where and how did we test? Our test loop

Real riding and handling in wind and weather on different surfaces instead of Excel tables, theoretical data and lab tests. In our evaluation of the test field, we are guided by practical experience on test rides instead of parameters on paper. That’s why we tested all bikes on a predefined test track around St. Vigil in the Dolomites. Between the Piz de Plaies, the Albergo Alpino Pederü and the Lavarella mountain hut, we found perfect test conditions in the Fanes Sennes Braies nature park. Our test loop offered everything that a gravel ride and a mountain bike tour can offer. These were the sections of the test track:

The mountain pass

A perfectly asphalted mountain road with a gradient of up to 15%. Here, the bikes had to prove their climbing skills uphill. On the subsequent downhill, we tested the bike’s handling at high speeds, through wide bends and during evasive manoeuvres. Also important: how fast does a bike get up to speed and how well can it maintain it?

The gravel section

Get off the asphalt and rattle over the gravel. The gravel section of our test loop combined a mix of compact gravel sections and fist-sized, loose gravel. Short steep ramps, off-camber turns and several gravel hairpins provided ample opportunity to scrutinise the test bikes’ handling. We paid attention to how agile a bike is on a scale from lively/playful to smooth/sluggish. Does it get choppy or bounce around when changing direction quickly? How is the rider’s steering input translated and how does the bike’s cornering behaviour change at different speeds? A good all-round bike is characterised by a harmonious balance between agility and smoothness. The rider’s input should be directly implemented without unsettling the bike.

Explorer mode through the national park

The bikes had to show what they’re capable of on detours over various forest paths and trails. On the flat, over long distances on root carpets, through soft sand or over trails, the bikes show whether they can manage the balancing act between comfort and propulsion. Traction is king, while a bike that is easy to control also helps you to reach your destination in a more relaxed manner and to enjoy the ride more. Only those who can rely 100% on their kit are in a position to discover new things without hesitation and to reach their destination safely.

In addition to traction, comfort is also important. Too much compliance can turn even the most beautiful tour into a spongy nightmare. The same applies to unnecessarily stiff bikes that pass on the smallest bump unfiltered to the rider. For us, it was therefore crucial to look at the comfort level of the entire bike. The interaction between the damping of tires and frameset and the compliance of components was important for us in order to clarify the question of how good the damping of the overall system is.

The trail: Let’s get down to business

The Dolomites are known for their endless trails. Instead of riding on blocked-up high alpine trails with chunks of scree the size of a handball and the risk of falling, our test bikes proved themselves on flowing trails that have been specifically developed for mountain bikes. Bends, braking bumps, steep sections and the odd jump revealed the strengths and weaknesses of the bikes in this terrain.

The tops and flops of our group test

It’s often the details that make the difference: successful integration, first-class ergonomics and carefully selected components. Here you can find all the tops and flops of the bikes from our group test of mountain and gravel bikes.

Tops

With a huge 520% range, the SRAM GX Eagle AXS groupset of the BMC Twostroke ensures easy climbing, even in alpine terrain. Shifting is fast and imperceptible. Great!

With clearances for tires up to 700 x 50C, the frameset of the Canyon Grizl offers decent amounts of space. The frame is also compatible with gravel suspension forks like the RockShox Rudy Ultimate.

The ergonomics of the 440 mm Zipp Service Course 70 XPLR handlebar on the Lauf True Crit convinced all our testers. A highly recommended aluminium handlebar.

Trek’s exclusive IsoStrut shock is an innovative suspension design that generates 60mm of damped and tunable travel. At its heart is a shock that is integrated into the top tube and a pivotless rear triangle with flex stays.

MTT from front to rear on the BMC URS LT ONE, so you’re better isolated from small vibrations and undulating compressions.

Thanks to the 1x drivetrain on the Fustle, the left Shimano lever isn’t needed for shifting and is instead used for the 120 mm travel PRO Koryak dropper post. It moves the saddle properly out of the way and so you’re free to let loose on the trail!

Flops

The SRAM Level TLM brakes of the BMC Twostroke couldn’t convince our testers due to their limited braking power and poor endurance over long descents.

The limited tire clearance of the carbon frame unnecessarily restricts the Lauf’s range of applications. Here, just like the suspension fork, there should be room for tires up to 700 x 50C.

We couldn’t get the combination of WTB Riddler tires and HUNT 4 Season Gravel Disc X-Wide aluminium wheels on the Fustle to seal properly during our test. Other than that, the tire suits the bike well!

The shifting performance of the Shimano GRX RX800 groupset on the Canyon and the Fustle is comparatively spongy and falls behind the rest of the test field.

The integrated seat post clamp of the BMC URS LT ONE is a visual delight. If you want to adjust the saddle height, you’ll have to free up the clamp with a hearty blow to the saddle. Thankfully, most riders won’t have to do that every day.

2x brake lines, 1x shift cable, 2x cables for the lockout. The cockpit of the Trek is a hive of activity. Compared to the competition, it’s also a bit too cluttered.

The most versatile bike concept in the test: Lauf True Grit SRAM XPLR Edition

Boom! After an intensive week of testing in South Tyrol, the Lauf True Grit SRAM XPLR Edition comes out on top as the most versatile bike concept. No other concept in the test field makes as few missteps in as wide a range of areas. If you really only want to have one bike in your garage and want to keep all options open from road to mountain bike trails, you can’t ignore a bike concept like the Lauf True Grit.

Second place for the mountain bike fully: Trek Supercaliber 9.8 GX

Just as versatile, but a bit more off-road: the Trek Supercaliber 9.8 GX. Those who generally avoid roads and are happy with the mountain bike hand position will find the better concept here compared to a gravel bike. However, in terms of versatility, the Trek ultimately has to admit defeat to the Lauf concept by a narrow margin. A very strong second place!

Are all the other bikes losers?

Or, is it a bad sign if the remaining four bike concepts from the comparison test are not as versatile as the Lauf or the Trek? Not at all! A specialised bike is not necessarily a bad bike. By no means does every bike have to be an all-rounder, because conversely, not all of you are interested in always wanting to do everything. Versatility always has its price! A bike that wants to be good everywhere is often not the best anywhere. As such, if you have a clearly defined area of use in mind for the bike you want, a specialist in this one area will most likely always be better than an all-rounder that covers the widest possible range of uses. It’s just a shame when a specialised concept like the Fustle’s doesn’t work out completely, in this case due to the components fitted to it. So no, the other bikes aren’t losers! You should take a close look at the range of use cases we recommend for them and decide accordingly which is the best bike concept for you.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, we would be stoked if you decide to support us with a monthly contribution. By becoming a supporter of GRAN FONDO, you will help secure a sustainable future for high-quality cycling journalism. Click here to learn more.

Words: Benjamin Topf, Felix Stix Photos: Benjamin Topf, Peter Walker